Vesicoureteral reflux

Updated: 2025-02-05

Overview

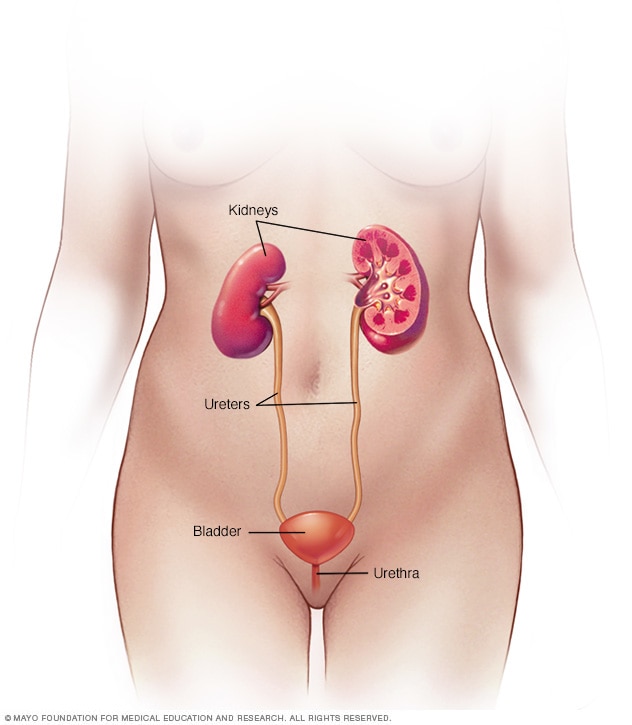

Female urinary system

The urinary system includes the kidneys, ureters, bladder and urethra. The urinary system removes waste from the body through urine. The kidneys are located toward the back of the upper stomach area. They filter waste and fluid from the blood and produce urine. Urine moves from the kidneys through narrow tubes to the bladder. These tubes are called the ureters. The bladder stores urine until it's time to urinate. Urine leaves the body through another small tube called the urethra.

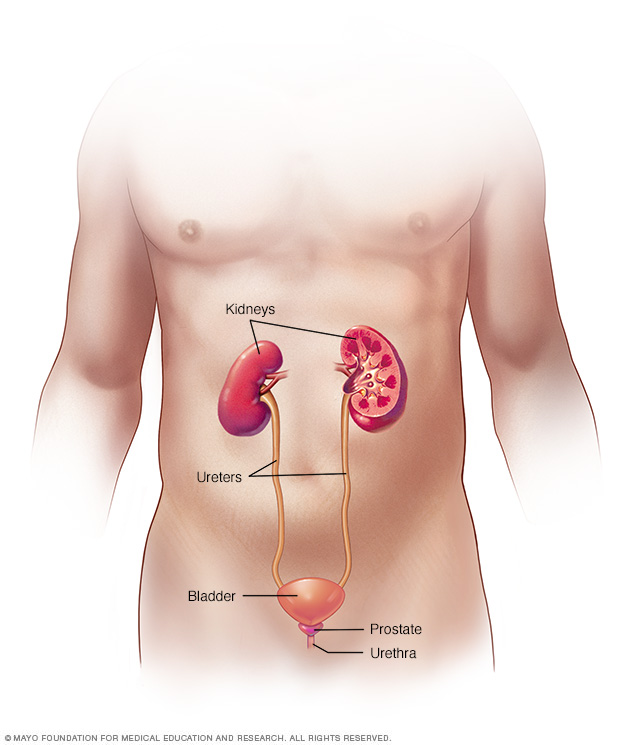

Male urinary system

The urinary system includes the kidneys, ureters, bladder and urethra. The urinary system removes waste from the body through urine. The kidneys are located toward the back of the upper stomach area. They filter waste and fluid from the blood and produce urine. Urine moves from the kidneys through narrow tubes to the bladder. These tubes are called the ureters. The bladder stores urine until it's time to urinate. Urine leaves the body through another small tube called the urethra.

Vesicoureteral (ves-ih-koe-yoo-REE-tur-ul) reflux means that some urine flows in the wrong direction once it reaches the bladder. It flows back up tubes called ureters that connect the kidneys to the bladder. Typically, urine flows from the kidneys through the ureters down to the bladder. It's not supposed to flow back up.

Most often, vesicoureteral reflux is found in infants and children. Some are born with vesicoureteral reflux due to an issue with the structure of one of the two ureters. Others develop the condition later for reasons such as the bladder not being able to empty fully.

With vesicoureteral reflux, urine can carry germs from the bladder up to the kidneys. That raises the risk of urinary tract infections (UTIs). UTIs can happen in any of the organs that make urine and remove it from the body. These infections can cause symptoms such as a strong need to urinate and pain while urinating. Without treatment, UTIs can lead to kidney damage.

Some children who are born with vesicoureteral reflux outgrow it. Others need treatment such as medicine or surgery. The goal of treatment is to prevent kidney damage and more UTIs.

Symptoms

Vesicoureteral reflux symptoms often are due to a urinary tract infection (UTI). A UTI doesn't always cause symptoms, but most people notice some.

These symptoms can include:

- A strong, constant urge to urinate.

- A burning feeling when urinating.

- The need to pass small amounts of urine often.

- Cloudy urine.

- Fever.

- Pain in the side, groin or stomach area.

Babies and some small children with UTIs can't tell adults what their symptoms feel like. But they may have:

- A fever for no clear reason.

- Lack of hunger.

- Fussiness.

As a child gets older, vesicoureteral reflux that doesn't get treated can lead to:

- Bed-wetting.

- Constipation or loss of control over bowel movements.

- High blood pressure.

- Protein in urine.

- Urgent need to urinate or urinating more often than usual.

- Leaking urine by accident, also called urinary incontinence.

Another symptom of vesicoureteral reflux is swelling of one or both kidneys. This swelling is called hydronephrosis. It's caused by the backup of urine into the kidneys. An imaging test called an ultrasound often finds this swelling before a baby is born.

When to see a doctor

Call a healthcare professional right away if your child has any UTI symptoms, such as:

- A strong, persistent urge to urinate.

- A burning sensation when urinating.

- Pain in the stomach area, groin or side.

- Upset stomach or vomiting.

Call your healthcare professional about fever if your child:

- Is younger than 3 months old and has a rectal temperature of 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit (38 degrees Celsius) or higher. A child 2 months old or younger may need emergency care.

- Is 3 months or older and has a fever of 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit (38 degrees Celsius) or higher without other symptoms that lasts more than 24 hours.

- Is also eating poorly, has had major changes in mood, or looks or acts very sick.

Causes

There are two main types of vesicoureteral reflux, and they have different causes.

-

Primary vesicoureteral reflux. Children are born with this more common type of reflux. It's caused by a problem with the valve that usually keeps urine from flowing backward from the bladder. The valve doesn't close well. This lets urine flow back up tubes called ureters that carry urine from the kidneys down to the bladder.

As children grow, the ureters lengthen and straighten. That may help the valve work better and correct the backflow of urine over time. This type of vesicoureteral reflux tends to run in families. So it may be genetic. But the exact cause isn't known.

- Secondary vesicoureteral reflux. This type of reflux most often happens because the bladder doesn't empty properly. There can be many reasons for this. For example, a fold of tissue may block urine from fully leaving the bladder. Or muscles that connect the bladder to another tube called the urethra may become too narrow. Or the nerves that control the bladder's ability to empty may become damaged.

Risk factors

Risk factors for vesicoureteral reflux include:

- Bladder and bowel dysfunction (BBD). Children with BBD hold their urine and stool. They also get repeated urinary tract infections. That can contribute to vesicoureteral reflux.

- Race. White children appear to have a higher risk of vesicoureteral reflux than do Black children.

- Sex assigned at birth. In general, girls have a much higher risk of having this condition than boys do. The exception is for vesicoureteral reflux that's present at birth. This is more common in boys.

- Age. Infants and children up to age 2 are more likely to have vesicoureteral reflux than older children are.

- Family history. Primary vesicoureteral reflux tends to run in families. Children whose parents had the condition are at higher risk of it. Siblings of children who have the condition also are at higher risk. So your healthcare professional may recommend screening tests for siblings of a child with primary vesicoureteral reflux.

Complications

Kidney damage is the main health concern, also called complication, that can happen with vesicoureteral reflux. The worse the reflux, the more serious the complications are likely to be.

Complications may include:

- Kidney scarring. Without treatment, UTIs can lead to lasting damage to kidney tissue known as scarring. Extensive scarring may lead to high blood pressure and kidney failure.

- High blood pressure. The kidneys filter waste from the bloodstream. So damage to the kidneys can cause waste to build up. That in turn can raise blood pressure.

- Kidney problems. Scarring can cause an affected kidney to have trouble filtering blood. This may lead to kidney failure, meaning the kidney loses its filtering ability. This life-threatening condition can happen quickly, also known as acute kidney injury. Or it can develop over time, also called chronic kidney disease.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis involves the steps that your healthcare professional takes to find out if your child has vesicoureteral reflux. A urine test can reveal whether your child has a UTI. Other tests may be needed, including:

- Kidney and bladder ultrasound. This imaging test uses high-frequency sound waves to make images of the kidney and bladder. Ultrasound can find out if parts of either organ don't look regular. This same test often is used during pregnancy to track a baby's development. It also may reveal swollen kidneys in the baby. That can be a symptom of primary vesicoureteral reflux.

-

Specialized X-ray of the urinary system. This test is called a voiding cystourethrogram, or VCUG. It uses X-rays of the bladder when it's full and when it's emptying to spot clues to health issues. During the test, your child lies back on an X-ray table. A healthcare professional places a thin, flexible tube called a catheter through the urethra and into the bladder. Contrast dye is injected into the bladder through the catheter. Then the bladder is X-rayed.

Next, the catheter is removed so that your child can urinate. More X-rays are taken of the bladder and urethra during urination. This lets the healthcare professional see whether the urinary tract is working correctly. The test likely won't be painful. But the healthcare professional may give your child calming medicine called a sedative first. Risks of this test include discomfort from the catheter or from having a full bladder. The test may raise the risk of a new urinary tract infection. It also may expose your child to a small amount of radiation.

- Nuclear scan. This test uses a tracer called a radioisotope. The scanner detects the tracer and shows whether the urinary tract is working correctly. Risks include discomfort from the catheter and discomfort during urination. The test involves less exposure to radiation than does a VCUG.

Try to get tested at a center that has lots of experience using catheters. If your baby or young child needs a VCUG, choose a center that knows how to minimize radiation exposure.

Grading the condition

After the tests, healthcare professionals grade the degree of reflux. With the mildest reflux, urine backs up only to the ureter. This is called grade 1. The most serious reflux involves kidney swelling, called hydronephrosis, and twisting of the ureter. This is known as grade 5.

Treatment

Treatment options for vesicoureteral reflux depend on how serious the condition is. Children with mild primary vesicoureteral reflux may outgrow it in time. In this situation, your child's healthcare professional may recommend a wait-and-see approach.

For more-serious vesicoureteral reflux, treatment options include medications or surgery.

Medications

UTIs need to be treated quickly with antibiotics. These medicines help keep the germs that cause the infection from moving to the kidneys. To prevent UTIs, healthcare professionals also may prescribe antibiotics at a lower dose than for treating an infection.

A child being treated with medicine needs to be watched for as long as it takes to finish the medicine. This includes getting regular physical exams and urine tests to detect UTIs that happen despite the antibiotic treatment. These are known as breakthrough infections. Your child also may get occasional scans of the bladder and kidneys to check if your child has outgrown vesicoureteral reflux.

Surgery

Surgery may be needed if vesicoureteral reflux doesn't get better with medicine. For instance, it may be a treatment option if your child keeps getting UTIs with fever. Surgery can fix the leaky valve between the bladder and each affected ureter. A valve condition keeps the valve from closing and preventing urine from flowing backward.

There are various ways of doing surgery. Each method usually involves the use of medicine called general anesthetic. This medicine puts your child in a sleeplike state and prevents pain during surgery. Methods of doing surgery include the following:

- Open surgery. This is the most common type of surgery to repair the valve between an affected ureter and the bladder. The surgeon repairs the valve through a cut, also called an incision, in the lower stomach area. Afterward, your child likely will need to recover in the hospital for a few days. During this time, a catheter is kept in place to drain your child's bladder. Vesicoureteral reflux may continue in a small number of children who get surgery. But the reflux often gets better without need for more treatment.

-

Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery. This surgery also involves repairing the valve between the ureter and the bladder. But it's done using small incisions. The surgeon uses a computer to control robotic arms equipped with a camera and surgical tools. These arms let the surgeon operate with precise movements. Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery may irritate the bladder less than open surgery. And the incision scars may be less visible once they heal.

But robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery may not have as high of a success rate as open surgery does. It also is linked with a higher rate of complications, such as urine leakage, than is open surgery.

-

Endoscopic surgery. In this surgery, the doctor inserts a lighted tube called a cystoscope through the urethra. This lets the surgeon see inside the bladder. Then the surgeon injects a special gel around the opening of the affected ureter. The gel forms a bulge that can help strengthen the valve's ability to close properly.

This method doesn't involve incisions in the skin. So you may hear it called minimally invasive surgery. Endoscopic surgery carries fewer risks than does open surgery. And children who get endoscopic surgery often can go home the same day. This is known as outpatient surgery. But endoscopic surgery may not be as effective as open surgery.

Rarely, some children with serious vesicoureteral reflux need surgery to remove part or all of an affected kidney. This surgery is called nephrectomy. For instance, nephrectomy might be done if a kidney is badly infected and working poorly.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Lifestyle and home remedies can help ease symptoms of urinary tract infections. These infections are common with vesicoureteral reflux, and they can be painful. But you can take the following steps to ease your child's discomfort until antibiotics clear the infection:

- Encourage your child to drink fluids, especially water. Drinking water dilutes urine and may help flush out germs.

- Provide a heating pad or a warm blanket or towel. Warmth can help ease feelings of pressure or pain. If you don't have a heating pad, warm a towel or blanket in the dryer for a few minutes. Be sure the towel or blanket is just warm, not hot. Then place it over your child's stomach area.

If bladder and bowel dysfunction (BBD) plays a part in your child's vesicoureteral reflux, encourage healthy toileting habits. Have your child use the bathroom regularly. For instance, it can help to empty the bladder every 2 to 3 hours while awake. Also, try to prevent constipation. Have your child drink plenty of water and eat a diet that's high in fiber. If your child becomes constipated, talk with your child's healthcare professional about treatment choices. Medicine called a laxative may be an option. A laxative can soften stool or get the bowels moving.

Preparing for an appointment

Healthcare professionals usually spot vesicoureteral reflux as part of follow-up testing when an infant or young child has a urinary tract infection. Call your child's healthcare professional if your child has symptoms such as a long-lasting fever or pain or burning during urination.

Your child may be referred to a doctor called a urologist who finds and treats urinary tract conditions. Or your child may be referred to a doctor called a nephrologist who finds and treats kidney conditions.

Here's some information to help you get ready, and what to expect from your child's healthcare professional.

What you can do

Before your appointment, take time to write down key information, including:

- Symptoms your child has been having, and for how long.

- Information about your child's medical history, including other recent health problems.

- Details about your family's medical history, including whether any of your child's first-degree relatives — such as parents or siblings — have had vesicoureteral reflux.

- All medicines, vitamins or other supplements your child takes, including the doses.

- Questions to ask your child's healthcare professional.

For vesicoureteral reflux, some basic questions to ask your child's healthcare professional include:

- What's the most likely cause of my child's symptoms? Are there other possible causes, such as a bladder or kidney infection?

- What kinds of tests does my child need?

- How likely is it that my child's condition will get better without treatment? Or, if you recommend a certain treatment, what are its benefits and risks?

- Is my child at risk of complications from this condition? If so, how will you watch my child's health over time?

- What steps can I take to lower my child's risk of urinary tract infections?

- Are my other children at increased risk of vesicoureteral reflux?

- Do you recommend that my child see a specialist?

Feel free to ask other questions that occur to you during your child's appointment. The best treatment option for vesicoureteral reflux often isn't clear-cut. To choose a treatment that seems right to you and your child, it's important that you understand your child's condition. And be sure to ask the healthcare professional about the benefits and risks of each available treatment.

What to expect from your doctor

Your child's healthcare professional gives your child a physical exam. The healthcare professional is likely to ask you questions such as:

- When did you first notice your child's symptoms?

- Do these symptoms happen all the time or do they come and go?

- How bad are your child's symptoms?

- Does anything seem to improve these symptoms? What, if anything, appears to make the symptoms worse?

- Does anyone in your family have a history of vesicoureteral reflux?

- Has your child had any growth problems?

- What types of antibiotics has your child received for other infections, such as ear infections?

Be ready to answer these questions. It may give you extra time to talk about any points you want to spend more time on.